Qatar’s successful bid for the right to host the 2022 World Cup has put the Gulf state at the forefront of demands for legal changes to its labour regime that potentially could change the very nature of its society and politics and serve as a model for other countries in the region. The bid has also sparked the beginnings of long overdue debate of taboo issues, including rules governing citizenship and naturalization.

As a result, in a world in which mega sporting events largely fail to leave the kind of legal, social and political change that international sports associations like the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), the world soccer body, hope to spark, Qatar’s World Cup and more generally its greater sporting ambitions hold out the potential of being a rare success story.

In making taboo issues discussable, the awarding of the World Cup to Qatar virtually a decade before the event is scheduled to take place has already sparked change. It potentially initiated a process of change in a country in which concerns that stem from a demographic deficit have long prevented the country from confronting intractable issues head on and stalled progress towards proper rule of law.

The proof will be in the pudding since Qatar has so far talked the talk but failed to fully walk the walk. Tackling fundamental legal, social and economic problems associated with its kafala, or sponsorship system, that puts employees at the mercy of their employers has stalled despite the adoption of legal changes that streamline rather than reform the system. Qatar’s reluctance to address issues head on has led human rights and trade union activists to question Qatar’s sincerity in a series of reports that argued that change in the Gulf state six years after the awarding by FIFA of the 2022 hosting rights has been excruciatingly slow and too little too late.[2]

Qatari officials, expecting that they would be feted for their successful bid, were taken aback by the avalanche of criticism that hit them almost immediately after FIFA announced in December 2010 that the Gulf state would become the first Middle Eastern nation to host one of the world’s foremost sporting events.[3]

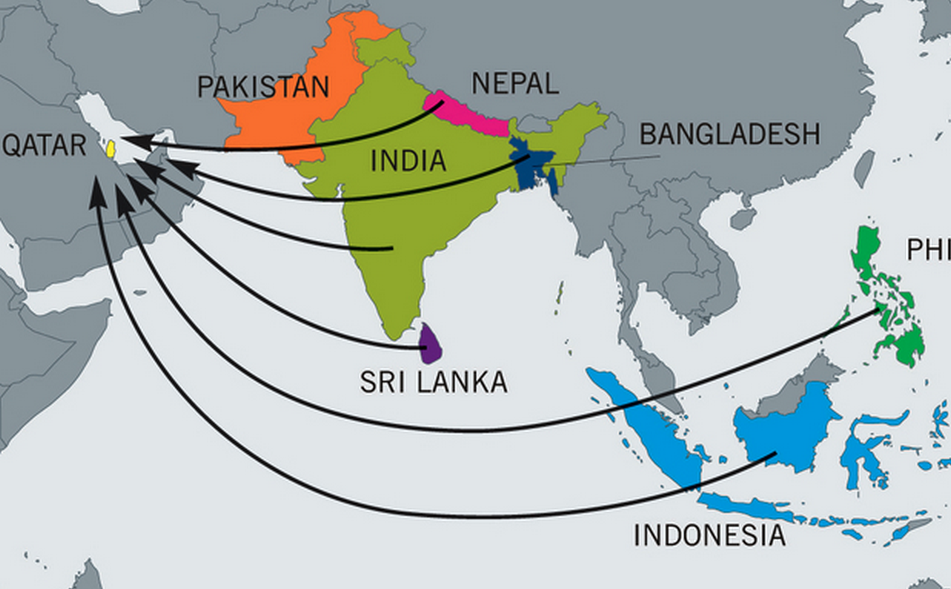

International and domestic Qatari debate has since focused alongside questions about the integrity of the Qatari bid on demands for legal reform enshrined in national legislation that would ensure improved working and living conditions of migrant workers, many of whom work on World Cup-related infrastructure projects.

The fallout of the debate has been felt moreover beyond Qatar as other Gulf states were forced to tinker with their own, equally onerous migrant worker and expatriate labour regimes. In some countries, particularly the United Arab Emirates, the pressures to which Qatar was exposed, sparked discussion on broader social issues related to the demographic deficit in many of the region’s statelets where debate about citizenship and naturalization of foreigners had long been taboo.

Breaking taboos

To field an Olympic team that would earn Qatar its first ever Olympic medal, Qatar, a tiny state with a population of 2.3 million of which only 300,000 are citizens, granted 23 athletes from 17 countries citizenship in advance of the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games. They constituted the majority of the Gulf state’s 39-member team.

The athletes’ naturalization, their success notwithstanding, sparked debate about the principle of granting citizenship and who should be awarded the right in a country in which Qatari nationals account for a mere 12 percent of the population.[4] Naturalization was long a taboo subject given Qatari fear that it, like any kind of social or political change, could cost the citizenry loss of control of their state and society. Those fears were enhanced by the fact that Qataris realized that there were no easy solutions to a demographic deficit that would prove unsustainable in the long term.

The Qatari debate was echoed in the UAE where Sultan Sooud al-Qassemi, an erudite intellectual, businessman, art collector and member of the ruling family of Sharjah, provoked controversy in articles that advocated a rethinking of restrictive citizenship policies that were likely to exacerbate rather than alleviate long-term problems associated with the demographic deficit. Echoing a sentiment that is gaining traction among Internet-savvy youth who are exposed to a world beyond the confines of the Gulf, Al-Qassemi noted that foreigners with no rights had, over decades, contributed to the UAE’s success. “Perhaps it is time to consider a path to citizenship for them that will open the door to entrepreneurs, scientists, academics and other hardworking individuals who have come to support and care for the country as though it was their own,” he argued. [5]

To be sure, debate about the Gulf‘s labour regime and the demographic deficit in much of the Gulf has long preceded the awarding of the World Cup to Qatar. Yet, it took the awarding to propel issues of social, political and legal change to prominence on international and domestic agendas. The awarding also forced Qatar to become the first, and so far, only, Gulf state to engage rather than ignore its critics.

Despite the regular brief arrests of foreign journalists visiting Qatar to report on migrant labour and greater pressures on critics based in the Gulf state, Qatar has by and large sought to engage human rights and trade union activists in shaping internationally accepted living and working standards for migrant workers who account for a majority of its populations.

Such standards have been adopted by at least three major Qatari institutions: Qatar Foundation, the 2022 Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy that is responsible for organizing the World Cup, and Qatar Rail. Qatar’s engagement and the fact that it has allowed activists to do independent research and launch their hard-hitting critical reports at news conferences in Doha contrasts starkly with approaches in other Gulf states that jail their domestic critics and bar entry to foreign detractors.

International criticism has focussed on four areas: Qatar’s failure to enshrine in national legislation those standards adopted by major organizations that are not yet part of the country’s legal code; the need to expand reforms to include a worker’s right to free movement from one employer to another and to travel in and out of the country; the granting of more political rights such as free trade union organization and collective bargaining; and effective implementation of reforms.

The pressure for legal reform, if not abolishment of the kafala system, is steadily building. The International Labour Organization (ILO) in March 2016 gave Qatar a year to implement labour reform. The ILO warned that it would establish a Commission of Inquiry if Qatar failed to substantially reform its controversial labour regime.[6]

Such commissions are among the ILO’s most powerful tools to ensure compliance with international treaties. The UN body has only established 13 such commissions in its century-long history. The last such commission was created in 2010 to force Zimbabwe to live up to its obligations.[7]

At about the same time, FIFA created a watchdog to monitor the living and working conditions of migrant labour employed on World Cup 2022-related construction sites. The watchdog, which has yet to make a pronouncement, constituted the first concrete follow-up to a report by Harvard University professor John Ruggie, a renowned human rights scholar, that called on FIFA to “consider suspending or terminating” its relationship with World Cup hosts who fail to clean up their human rights records.

Finally, this year’s annual report by the US State Department on human trafficking provided Qatar with yet another roadmap to counter World Cup-related international criticism of its labour regime. The report took Qatar to task on three fronts: the implementation of existing legislation and reforms, its failure to act on a host of issues that would bring the Gulf state into compliance with international labour standards, and its spotty reporting.[8]

The report noted that many migrant workers, despite a ban on forcing employees to pay for their recruitment and the withdrawal of licenses of some recruitment agencies, continue to arrive in Qatar owing exorbitant amounts to recruiters and at times have been issued false employment contracts.

A ministerial committee moreover recommended the establishment of a committee that would ensure regulation of domestic workers, who in Qatar, like in most Gulf states, are viewed as the most vulnerable segment of the workforce because labour laws and reforms do not apply to them. The State Department report acknowledged that Qatar had initiated its first prosecutions with the conviction of 11 people charged with trafficking, including ones related to domestic workers.

An initial roadmap

The US agency said that many workers continued to complain of unpaid wages even though Qatar introduced a wage protection system in November 2015 that obliges employers to pay their employees electronically in a bid to ensure that they are paid on time and in full. The report further quoted a 2014 study by Qatar University’s Social and Economic Survey Research Institute as saying that 76 percent of expatriate workers’ passports remained in their employers’ possession, despite laws against passport confiscation.

Much of the roadmap distilled from the State Department’s criticisms and recommendations involve measures that the government could take with relative ease. They include:

- Creation of a lead agency for anti-trafficking efforts to replace the Qatar Foundation for Protection and Social Rehabilitation (QFPSR) that was removed as the government’s central address, and expansion of the new agency’s responsibilities beyond the abuse of women and children;

- extending labour law protection to domestic workers and ensuring that any changes to the sponsorship system apply to all workers;

- enforcing the law banning and criminalizing the withholding of passports by employers;

- providing victims with adequate protection services and ensuring that shelter staff speak the language of expatriate workers;

- reporting of anti-trafficking law enforcement data as well as data pertaining to the number of victims identified and the services provided to them; and

- providing anti-trafficking training to government officials.

The roadmap would allow Qatar to take significant steps in some areas which would likely be domestically less sensitive. It would also allow Qatar to demonstrate that it is serious about implementation.

To be sure, the roadmap fails to address core concerns about Qatar’s reforms to date that have focused on improving physical living and working conditions, ensuring timely payment of wages and salaries, and countering human trafficking. Qatar sought to address demands for less restrictive contractual terms by adopting a new law that comes into force in December.

Never missing an opportunity to miss an opportunity, the new law replaces indefinite-term labour contracts with five-year agreements. Workers, however, would not be allowed to break the contract or change employers before the contract has expired. Workers would also continue to need their employer’s permission to travel but the reforms introduce a government appeal mechanism. The law abolishes the requirement that employees leave the country for two years before seeking new employment in Qatar if an employer refuses to grant a no objection certificate.

The law upholds the institution of an exit visa but inserts the state into equation the by obliging employees to inform the interior ministry three days before their planned departure. The ministry rather than the employee would then obtain the employer’s consent. The law also grants employees the right to appeal if the employer refuses permission.

Like the roadmap, there are various steps that Qatar could have taken in the last six years that would have bought it a degree of confidence in its sincerity and avoided at least some of the reputational damage the Gulf state suffered. Three major steps that come to mind are incorporation in national legislation of those elements of the standards adopted by the Supreme Committee and others that are not yet part of Qatari law; a drastic and rapid rather than a gradual increase of the number of labour inspectors employed to ensure implementation of newly adopted standards; and adoption of a system modelled on the United States’ Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC).

One reason Qatar has been reluctant to abolish the exit visa is the fact that the Gulf state has few extradition treaties with other countries. As a result, businessmen who hire foreigners to operate their businesses and give senior managers access to company bank accounts fear that a manager could empty an account and escape the country. Critics suggest that the government could have addressed that concern by offering businesses FDIC-type arrangements that guarantees bank deposits up to a certain amount.

To be fair, employer-specific visas are not unique to the Gulf. H2-B in the United States tie low-skilled seasonal workers to particular employers, and do not allow immediate job-to-job transitions after a contract expires.[9]

Liberalizing the Qatari labour regime also has economic and social consequences as is evident in the United Arab Emirates. In 2011, the UAE abolished exit visas and allowed employers to renew a migrant’s visa upon contract expiration without written permission from the initial employer. A study in 2014 concluded that the reforms raised workers’ income on average by ten percent and perhaps more alarmingly to Qatari and other Gulf nationals, reduced the number of foreigners that returned home after their contracts had ended.[10]

Adoption of creative measures could have eased the Catch-22 situation that Qatar appears to be gliding into. Spotlighted by its hosting of the World Cup, Qatar’s international reputation has been marred by perceptions that it is not doing enough to adopt globally accepted labour standards. Yet, at the same time it is in many ways frozen by fear and unable to come up with solutions for a demographic problem that can only be tackled with creative approaches that inevitably will change the nature of its society.

“Qatar has the financial means to make the real reforms, ensure safe work and decent wages, and the international community is ready to help when the government finally shows that it is serious,” said International Trade Union Confederation General Secretary Sharan Burrow.[11]

A double-edged sword

The international criticism is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it leverages Qatar’s World Cup to move the Gulf state towards some degree of legal and social reform. On the other, the activists’ demands fuel widespread fears among Qatari nationals, shared by populations across the region, that they will lose control of their culture, society and state if they open the Pandora’s Box of greater rights for non-nationals.

Those fears were reflected by Qatar’s largely foreign-born Olympic team whose naturalization and success sparked questions among non-Qataris who have been resident in the Gulf state and whose children were born there but who have no real path to citizenship even though their skills and expertise are and will be needed as the country streamlines and diversifies its economy. Qatari naturalization law stipulates that foreigners who speak Arabic and have resided in the country (of which the majority is non-Arabic speaking even though Arabic is the official language) for 25 years can be considered for citizenship on a case-by-case basis.

Limited opportunity for citizenship puts many of the country’s non-Qatari residents in an emotional bind. They do not want to “rock the boat” for themselves and their families, yet their existence remains precarious. “This is where I was born, this is my home. I accept things as they are, but it does sting,” said a South Asian professional who was born and grew up in Qatar.[12]

Ironically, one positive social and political fallout of Qatar’s sports strategy is that the South Asian’s sentiment is beginning to be reflected among some Qatari youth who are more willing to openly discuss sensitive issues.

Referring to Qatar’s 14-member Olympic handball team, 11 of whom are naturalized citizens, public sector employee Hamed Al-Khater asked on Twitter: “If these guys get naturalized then what about doctors, scientists, engineers, academics and artists? Don’t they add more value to society?”[13]

In another taboo-breaking incident, Doha News, against the backdrop of persistent questions in the Western soccer fan community about how Qatar would deal with gays attending its World Cup, published an article entitled: “What it’s like to be gay and Qatari.”

Written by a man using the pseudonym Majid Al-Qatari (Majid the Qatari), the article asserted that gay Qataris disguised their sexuality by being publicly homophobic, but travelled abroad to be themselves. Majid suggested that gays often got married and raised families in what amounted to putting “a Band-Aid on a wound. The wife will get conjugal visits and the men will just go their own way.”[14]

Al-Khater’s question and Al-Qatari’s expose are noteworthy in a country where public discussion of these issues has long been taboo even if they likely constitute a minority view. A majority of Qataris see homosexuality as banned by Islam and question whether foreigners can ever become true nationals. They also fear that it would jeopardize national identity, conservative culture and deep-rooted tribal values.

Public sentiment was reflected in demands in 2015 for greater segregation of migrant workers who largely leave their families behind to seek employment in Qatar. Doha’s Central Municipal Council (CMC) recently called on the government to enforce more strictly a five-year old ban on blue-collar workers living in neighbourhoods populated primarily by families.

Widespread nationalist sentiment among Qataris largely opposes any legal reform involving issues that would tinker with Qatar’s social, economic and political system. It is largely supportive of its dynastic rule. As a result, it has sparked questions about the country’s use of sports as a public diplomacy effort that also employs the arts, commercial enterprises like Qatar Airways, and mediation of regional conflicts. Those questions have been expanded to the financial and social cost of the sports strategy at a time of reduced energy income, belt tightening and Qatar’s first budget deficit in 15 years.

“With most Qataris subscribing to Wahhabism, an ultra-conservative branch of Sunni Islam, the locals didn’t want to exchange their religious beliefs for cheap tourism dollars… While Qatar isn’t as religiously conservative as neighbouring Saudi Arabia, it’s also not that far removed. All Qataris are expected to wear their ‘national uniform’ while in public (a black abaya for women, a white thobe for men). Workplaces pause for daily prayers, and fraternizing between members of the opposite sex is generally discouraged,” said Mikolai Napieralski, a former writer for the Qatar Museums Authority.[15]

Cultural and political norms regularly cast a shadow over Qatar’s public diplomacy that as it progressed, would inevitably have led to legal reform. A five-metre high statue of French soccer player Zinedine Zidane, created by Algerian-born French artist Adel Abdessemed, was removed in 2013 from public view after conservative Qataris insisted that it amounted to idol worship, a violation of the Wahhabi worldview.

Enlisting the clergy

In a bid to build grassroots support for legal reform of Qatar’s labour regime, the government has enlisted the support of religious scholars. A panel of religious scholars, officials of Qatar’s government-sponsored human rights committee, and international labour activists called last year for a radical overhaul of the country’s controversial labour policies.[16]

By justifying the call on theological grounds and drawing on a parable of Omar Ibn al-Khattab, one of the 7th century’s first four successors of the Prophet Mohammed, widely viewed by even the most conservative or militant Muslims as the righteous caliphs, Sheikh Ali Al Qaradaghi made it more difficult for Qatar and other Gulf states to justify evading radical labour reforms.

Al Qaradaghi serves as secretary general of the International Union of Muslim Scholars (IUMS), a group headed by Sheikh Yusuf Qaradawi, one of the most popular religious leaders in the Muslim world.

Speaking at the Research Centre for Islamic Legislation and Ethics (CILE) of Hamad Bin Khalifa University’s Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies, Al Qaradaghi said: “We see (migrants) working for us … But there is no appreciation. There is no love dedicated to those people. The earth was made for all creatures, all human beings, not one category of people… Arab and Muslim countries ought to take care of those who provide long periods of service and participate in the building of these countries. We need to take care of these people.”

Al Qaradaghi called further for paying migrant workers, who account for a majority of the Qatari population, a living wage that was related to the cost of living in the Gulf. He said that a monthly wage of “QR 1,000 (USD 275), for example, in this country cannot be good enough,” according to Doha News.

Al Qaradaghi recounted an encounter between Omar Ibn al-Khattab and an elderly Jew who was begging. In response to the caliph’s question why he was begging, the man said that despite working for half a century he was unable to make ends meet. The caliph instructed his aides to give the man money on the grounds that he had not been treated fairly. Mr. Qaradaghi said the caliph’s gesture should serve as an inspiration for Gulf rulers and employers.

Rule of law vs common sense

Legal reform in Qatar is best served by pressure on the Gulf state that is measured and geared toward avoiding pushing Qataris into a defensive mode in which their backs stiffen and they are unwilling to engage or entertain criticism. It is a lesson learnt by human rights groups in their dealings with the International Olympic Committee and Saudi women’s sporting rights. The groups concluded that they only had a window of opportunity to spark change in the period immediate before an Olympics tournament and that their voice would not be heard in much of the four years between tournaments.[17]

Qatar appeared to be reaching a point at which it began to push back in the summer of last year when the country’s Shura or Consultative Assembly that nominally serves as a legislature raised objections to the law that introduced changes to the kafala system. The council took issue with provisions that dealt with the entry, exit and residency of migrant workers. Underlining Qatar’s refusal to be seen to be bullied, Al Sharq, a Qatari news portal, quoted council chairman Mohammed bin Mubarak Al Khulaifi as saying that there was no need to rush the draft law.[18] The law that was ultimately adopted conformed with many but not all of the council’s demands.

Qatar’s debates about labour, citizenship and art highlight the sensitivities involved in legal reforms that have far-reaching social, economic and political consequences. They also contextualize the role that the awarding of the World Cup, alongside other public diplomacy tools, has had in putting controversial issues in the public eye and initiating a process of change no matter how tentative and how much it appears often to involve cosmetic rather than real change. There is no guarantee what the outcome of those debates and the process will be. It nonetheless creates a dynamic that needs to play out and that potentially is the mechanism that will ultimately open the door to substantial legal reform.

That is also true for debates about the rule of law and the integrity of the Qatari World Cup bid that has been consistently questioned by the Gulf state’s critics, credible media reporting, and that is being investigated by Swiss judicial authorities and could become part of the US Justice Department’s investigation into corruption in global soccer governance.

Qatar spent a multitude of money on its World Cup bid in comparison to its competitors. Its decision to splash was not one simply taken by a bunch of oil-rich Arabs dressed in pyjamas with tea towels on their heads and dollars coming out of every pore in their bodies. Like all other bids, it was the result of a rational cost/benefit analysis. Unlike its competitors, Qatar’s reason for bidding was not simply soft power but a key element of its foreign and defence policy that makes it far more valuable.

Qatar recognizes that big ticket military hardware purchases will not allow it to defend itself. Qatar, moreover, despite closer relations with Saudi Arabia under Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, does not want to have to be totally dependent for its defence on external powers like the United States or regional powers like Saudi Arabia and Iran, both of which it views as much as neighbours as well as potential threats.

Qatar’s misfortune is that the integrity of its bid is in question at a time when it is becoming evident that bribery and corruption in World Cup bids was standard practice in FIFA. In fact, it was controversy over the Qatari bid that exposed the pervasiveness of corruption in global soccer governance.

The question is how one best extracts positive change out of a bad situation. Depriving Qatar of its hosting rights, as many of its critics have demanded, is unlikely but remains nonetheless a distinct possibility, and is certain not to produce social or political change. On the contrary, it would not only stiffen Qatari backs but also rally the support of the Muslim world that would view penalizing the Gulf state as another Islamophobic affront.

Moreover, the fact of the matter is that most sporting mega-events leave a legacy of white elephants and debt. A recent video clip on social media illustrated dilapidated, discarded facilities in cities like Sarajevo and Athens that have hosted past Olympic Games.

The Qatar World Cup holds out the potential of change. It is a hope and process with no guarantee of success that deserves to run its course. Giving the process a chance of moving forward, would, if successful, provide far more significant and long-lasting results than depriving Qatar of its hosting rights on the grounds of justice having been done.