Two Bangladeshi and a Dutch trade union have sued FIFA in a Swiss court in legal proceedings that challenge the world soccer body’s awarding to Qatar of the 2022 World Cup because of the Gulf state’s controversial labour regime. The case could call into question group’s status as a non-profit and, if successful, open the door to a wave of claims against FIFA as well as Qatar and other Gulf states who employ millions of migrant workers.

The legal proceedings come at a crucial moment in efforts by trade unions and human rights groups to work with Qatar on reforming its kafala or labour sponsorship system that puts workers at the mercy of their employers.

Those efforts, a unique undertaking in a part of the world in which governments by and large refuse to engage and repress or bar their critics, have already produced initial results. The question is how far Qatar intends to push ahead with reform and to what degree it will feel the need to do so in a world in which the rise of populism has pushed human and other rights onto the backburner.

Trade unions and human rights argue that Qatar since winning World Cup hosting rights six years ago has had sufficient time to bring its labour system in line with international standards and that its moves so far fall short of that.

A key milestone alongside the trade unions’ legal action and a separate Swiss judicial inquiry into the integrity of the Qatari World Cup bid is a looming deadline set by the International Labour Organization (ILO) for Qatar to act on promises of reform that it has made.

The ILO warned last March that it would establish a Commission of Inquiry if Qatar failed to act within a year. Such commissions are among the ILO’s most powerful tools to ensure compliance with international treaties. The UN body has only established 13 such commissions in its century-long history. The last such commission was created in 2010 to force Zimbabwe to live up to its obligations.

The Netherlands Trade Union Confederation (FNV), supported by the Bangladesh Free Trade Union Congress (BFTUC) and the Bangladesh Building and Wood Workers Federation (BBWWF), filed their complaint against FIFA on behalf of a Bangladeshi migrant worker, Nadim Sharaful Alam.

Mr. Alam was forced as is the norm in recruitment for Qatar to pay $4,300 to a recruitment agency in violation of Qatari law and FIFA standards that stipulate that employers should shoulder the cost of hiring. To raise the money, Mr. Alam had to mortgage land he owned, according to FNV lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld. Mr. Alam is also demanding compensation for being the victim of “modern slavery,” Ms. Zegveld said.

The FNV said in a statement that it wanted the court to rule that “FIFA acted wrongfully by selecting Qatar for the World Cup 2022 without demanding the assurance that Qatar observes fundamental human and labour rights of migrant construction workers, including the abolition of the kafala system.” FIFA is a Swiss incorporated legal entity.

The trade unions’ further demand that the court order FIFA to ensure that in the run-up to the World Cup workers’ rights are safeguarded by pressuring the Gulf state to enact and implement adequate and effective labour reforms takes on added significance following the group’s decision to take over responsibility for preparations of World Cups starting with the Qatar tournament.

A Swiss government-sponsored unit of the Paris-based Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which groups 34 of the world’s richest countries, last year defined FIFA as a multi-national rather than a non-profit that was bound by the OECD’s guidelines. The decision meant that the soccer group would be responsible for upholding of the human and labour rights of workers employed in Qatar on World Cup-related projects. A court ruling upholding that principle would reinforce FIFA’s status as a business rather than a non-governmental organization.

FIFA has repeatedly said that it was “fully committed to do its utmost to ensure that human rights are respected on all FIFA World Cup sites and operations and services directly related to the FIFA World Cup.” FIFA has recently included provisions for labour standards in World Cup contracts that kick in with the 2026 tournament.

The decision to take on responsibility for World Cups means that FIFA no longer can hide behind assertions that it has no legal authority to impose its will on host countries. In a letter to Ms. Zegveld and the trade unions’ Swiss lawyers date 16 October 2016, FIFA Deputy Secretary General Marco Villiger asserted however that “FIFA refutes any and all assertions…regarding FIFA’s wrongful conduct and liability for human rights violations taking place in Qatar.” Ms. Zegveld noted that FIFA had refrained from denying the violations themselves.

A recent survey of construction companies involved in World Cup-related infrastructure projects in Qatar called into question whether the Gulf state and FIFA were doing all they could do to enforce international labour standards.

Less than a quarter of the 100 companies approached for the survey by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre deemed it appropriate to respond. Less than 40 percent publicly expressed a commitment to human rights and only 17 percent referred to international standards. Only three companies publicly acknowledged rights of migrant workers.

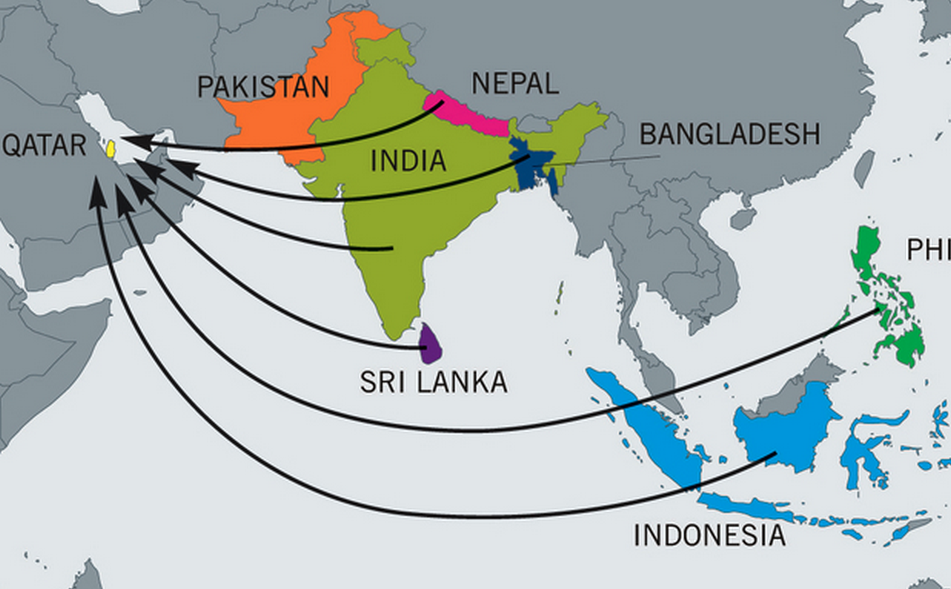

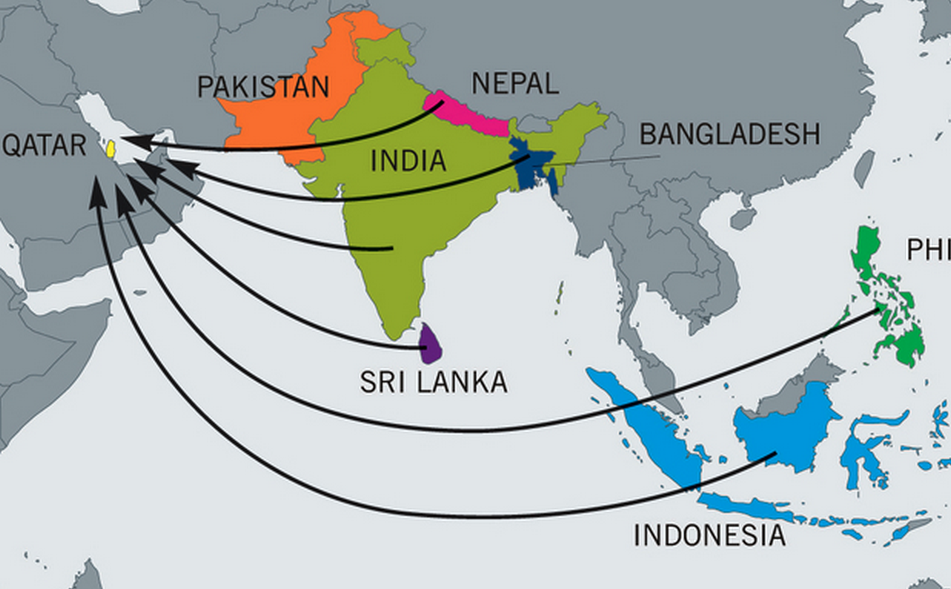

A human rights researcher with extensive experience in studying recruitment of migrant labour in Asia said the system was controlled by an international crime syndicate that benefitted from collusion between corrupt senior government officials, company executives, and recruitment agencies that cooperated across national borders at the expense of millions of unskilled workers. “Billions of dollars are involved, all off the books, not taxed that come from migrant workers,” the researcher said.

A trade union court victory could open the door to an avalanche of cases by migrant workers demanding compensation for illegal recruitment practices as well as being victims of a system that curtails freedom of contract as well as basic human freedoms and workers’ rights. Those cases could target not only FIFA but also Qatar and other Gulf states that operate a kafala system. “This could just be the beginning,” said a trade union activist.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is a senior fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, co-director of the University of Würzburg’s Institute for Fan Culture, and the author of The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer blog, a recently published book with the same title, and also just published Comparative Political Transitions between Southeast Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, co-authored with Dr. Teresita Cruz-Del Rosario.